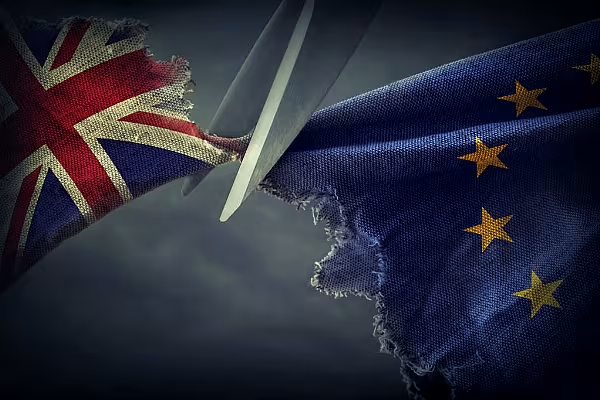

In our World Wide Webb reports, ESM's senior reporter Ben Webb takes a sideways look at some of the issues affecting the retail and FMCG industries. In this week's edition, he examines the issues British retailers could face when sourcing products in a post-Brexit world.

A pre-dawn trip to New Covent Garden Market, Britain’s largest food wholesaler, is a foodie delight.

The British late summer classics of apples, cherries and spuds and lots more are on show, but they now share pride of place with a colourful cornucopia of fresher and more exotic produce from the continent and beyond, from pink garlic to white peaches and from yellow beans to sweet greengages.

The smell of ripe fruit is intoxicating, but there is also something rotten in the state of the fresh market… it's called Brexit.

Like all Britain's supermarkets, this sprawling depot in south London, which has been supplying London since the UK joined the Common Market in the mid-70s, is facing new challenges to its supply chain.

When the umbilical connection to Europe is finally severed, what will be the impact of possible tariffs and delays on the price and quality of all the imported food. And who will pick the British produce? Most of the produce in the boxes proudly stamped with a Union Jack was collected from the field by workers from Eastern Europe.

This is not a eureka moment. The challenges are well known. The solutions, however, remain impossible to work out as no one knows exactly what's going to happen. As one game show host would ask: deal or no deal?

Different Paths

Simply put, a deal is looking less likely and a no deal situation will mean major disruption to supply chains.

"If the UK left the EU on 29 March 2019 without a deal there would be immediate changes to the procedures that apply to businesses trading with the EU. It would mean that the free circulation of goods between the UK and EU would cease," the government says.

Customs declarations would be needed, tariffs may appear and, the government warns, firms are likely to need to invest in new computer systems to track goods.

Supermarket bosses must be pulling their hair out. Roger Burnley, chief executive of Asda, has warned a hard Brexit could leave food rotting at the border.

“What would be scary is the prospect of any holdup at the border,” he says. “Any prospect of a hold-up would have very significant consequences. You’d be eating into the life of products with all sorts of implications for waste, for freshness, for quality.”

And even small hold-ups can have major knock-on effects. A two-minute delay, according to officials at Dover, Britain's busiest port, would lead to 27-kilometre long traffic jams on the Kent road network.

Given customs officials are not renowned for their laissez-faire attitude, especially when tasked with a new raft of red tape to police, two minutes might be optimistic.

When the delivery of fresh food is utterly reliant on speed, it's no surprise Burnley is not a lone voice.

“At the moment we put tomatoes on lorries in southern Spain, they drive for 24 hours and arrive directly in our distribution centres unencumbered,” Mike Coupe, Sainsbury's CEO told Bloomberg in a recent interview. “Anything that puts a barrier in that flow will increase the cost and reduce the freshness.”

Higher Food Prices, Lower Quality

Supermarkets are left to play a guessing game that involves a lot more than the logistics and cost of boxes of fresh fruit and vegetables.

It includes everything in the supply chain, from the huge variety of ingredients that go into other products, from premium private label ready meals to Marmite (remember the Marmite wars?) to materials such as cardboard.

The humble BLT – Bacon, Lettuce and Tomato – sandwich sums up the mess the UK sector finds itself in.

The British Sandwich Association warned about shortages of fresh food – and a so-called sandwich famine – if the UK does crash out of the EU.

The Brexit secretary Dominic Raab, however, boasted he would ensure adequate food supplies. He even suggested supermarkets could help by stockpiling food – a practice they have been minimising for decades.

The British Retail Consortium tartly replied, “Retailers do not have the facilities to house stockpiled goods and in the case of fresh produce, it is simply not possible to do so.”

Back to the BLT. The owner of Danepak, Britain's largest bacon supplier, once again raised the issue or rising prices. The EU tariff on non-EU bacon is about €68 to the kilo so Brits may have to pay an extra 15p on the price of a pack of eight rashers.

“Most of the ingredients in the BLT, in fact, will be imported – the tomatoes from the Netherlands and lettuce from Spain, Poland or even the US. Will they face delays at in-coming ports?

Raab makes it all sound so simple. “Who is credibly suggesting in a no-deal scenario the EU would not want to sell food to UK consumers?” he said. “Let me assure you that, contrary to one of the wilder claims, you will still be able to enjoy a BLT after Brexit.”

It have been be a catchy line, but post-Brexit, even the simplest snacks could leave a bitter taste in the mouth of consumers.

Read the previous World Wide Webb reports on Beer's Battle Of The Sexes and The Case For Plastic-Free Packaging.

© 2018 European Supermarket Magazine – your source for the latest retail news. Article by Ben Webb. Click subscribe to sign up to ESM: European Supermarket Magazine.